TL;DR A basic tenet of System Failure is, of course, that we live in a system that is about to fail. This essay considers two different historical perspectives to make the case that an historic economic collapse is imminent. Both the long trajectory of human history and the recent events of the 20th Century suggest that we are approaching the end of an era. But, in keeping with the relentlessly positive bent of System Failure, this essay also suggests reasons for great optimism.

When they write the history books, the year 2008 will mark the end of the end of the American Empire. After the sack of Rome in 410 A.D, people carried on thinking of themselves as Romans. Only with the passage of time did we decide on that year as the bookend to the Roman Empire. We live in a very similar twilight today as the Romans living post-410. The end has already come. The dominoes are already falling.

Partially because of the accelerating pace of technological change—which we will come to in a moment—and partially because of a gradual improvements in the quality of governance, we tend to think of history as having a plot or a theme. It’s like the saw-toothed pattern of a stock chart that gradually drifts upward over the long term, with many setbacks in the short term. There is clearly a rise to the long run of history.

Democracy

The societies that sprang up in the wake of the Agricultural Revolution generally had god-kings who ruled over them. The word of these god-kings was law, and the entire society more or less served to glorify his ego. Massive swaths of the populations were enslaved. The quality of life for people living inside these societies was of very little concern. The Roman Empire was the quintessential example. In many ways, it was the largest and final culmination of those old slave societies. That Empire put the entire known world under conquest. As legendary historian Will Durant put it, “Wealth mounted, but it did not spread; in 104 B.C. a moderate democrat reckoned that only 2,000 Roman citizens owned property.” This in a city of 5 million. Roman society eventually collapsed under the weight of that staggering inequality, leading to the sack of Rome in 410 when the Empire could no longer defend itself.

From the embers of the Roman Empire a new kind of society arose. Instead of the master-slave roles that dominated Roman society, Europeans began swearing fealty to feudal lords and working as peasants. You’d work for three days on your own behalf, and then three more days for your local feudal lord, and then on the seventh day you’d sit in church and hear how this was God’s will. Being a peasant was a lot better then being a slave. But Medieval society was still very rigid and based on heritage. Most people couldn’t aspire to be anything more than being a peasant, because their parents were peasants.

The Black Death put an end to all that. In the middle of the 14th century, the Bubonic plague sent half the peasantry to an early grave. The survivors realized that they could play one feudal lord off against another in a bidding war for their services. Of course, the aristocracy tried to enforce the old social order at sword-point. But inevitably, a more dynamic system emerged in which workers sold their labor to the highest bidder instead of swearing fealty to any one particular lord.

In the new system, things are produced and services are provided by people who are either employees or employers. This is, of course, the system we still live in today. It’s 600 years old at this point, and well past its prime. It’s the system that saw us through the Industrial Revolution. And there’s no question that it’s a superior system to its predecessors. Being an employee is far better than being a peasant, just as being a peasant was preferable to being a slave.

That general improvement, over the long haul, in the material conditions of people lends an arc to the human story. History is not cyclical, like the seasons of the year. Rather, history is the story of a fundamental inversion in progress. We are slowly graduating from top-down systems of political control to bottom-up systems. Like an iceberg rolling over in the open oceans, human society has been transiting from despotism toward democracy over the millennia.

But we haven’t arrived yet; it’s still a work in progress…

The system we are living in now is far from perfectly democratic. Notice that, while we affirm the value of democracy and demand it in most aspects of our lives, we still accept top-down systems of control at work. Our iceberg is still in the process of rolling over. We are living in a mixed transitional state. And it’s getting very long-in-the-tooth after 600 years. If historical trends persist, we should expect that our current employer-employee paradigm will be replaced by an even more democratic model.

Technology

And that leads us to Karl Marx’s prophecy. He noticed that technology presents an existential threat to the current system of employer-employee production. His observation was simple: the rapid pace of technological improvement unleashed by the capitalist system must logically be it’s undoing. The same historical trajectory outlined above led him to predict that a more democratic system would arise to replace it, in which the so-called “means of production” would be controlled directly by workers.

The old technology of yesterday becomes a platform on which the new technology of tomorrow is built. The gradual improvement of technology over time runs parallel to the gradual increase in democracy apparent in our history books. The dance between these two titanic historical forces was Marx’s obsession.

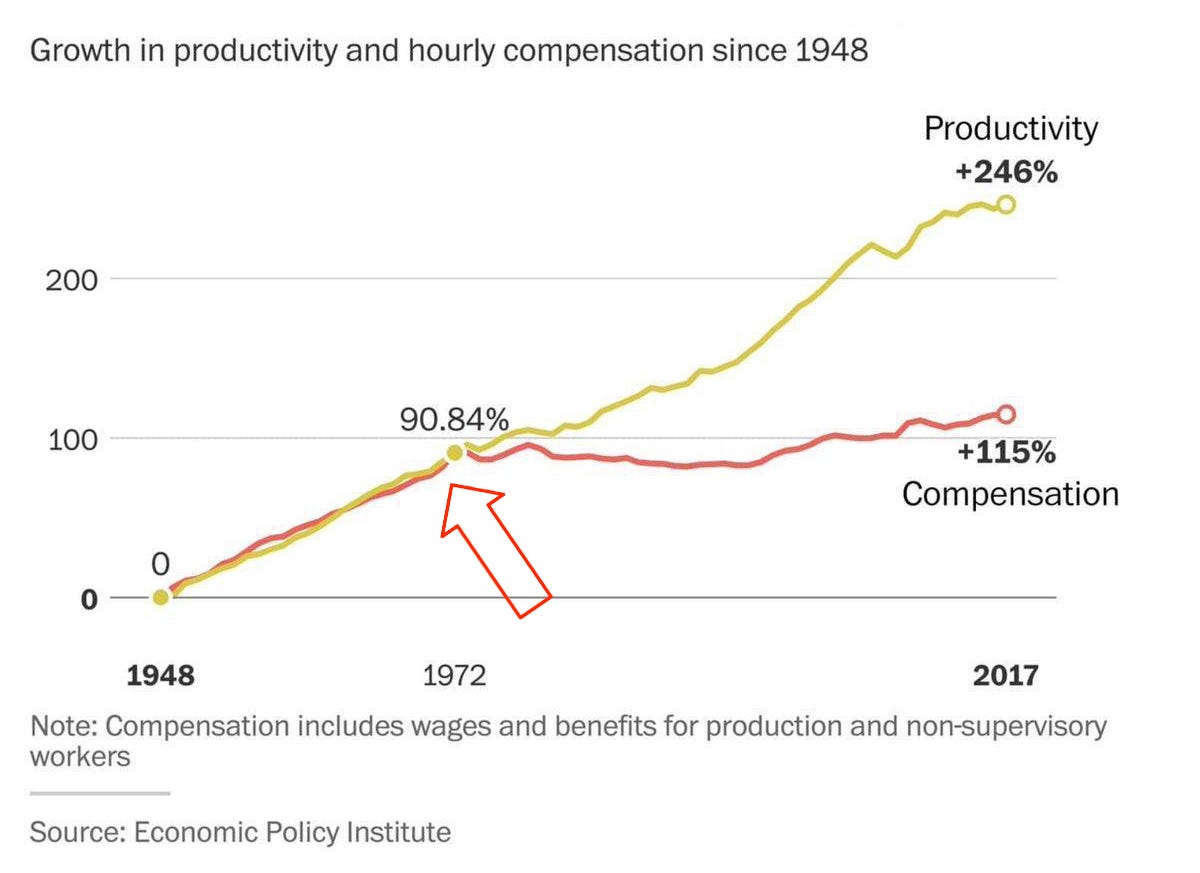

There is a huge incentive to push the pace of innovation in our current system of employers and employees. That’s because technology that saves on labor costs is incredibly valuable when production is happening at such a massive modern scale. As time wears on, Marx predicted that the rapid pace of technological innovation would render actual human workers less and less relevant to the production process. The dawning AI revolution is the ultimate example. Today, we can see his prophecy coming true in real time.

The historic irony at play here is that when business owners collectively pad their profits by firing redundant workers and replacing them with technology, they eradicate the consumer base that buys their products. On the whole, the employees who produce all the goods and services are the same folks who buy them—with the wages they earn. The less employers pay out in wages, the fewer consumers there will be for their products. This fundamental contradiction means there is a ticking countdown clock built into the capitalist system of production.

A more democratic system of production might have employees democratically voting on production decisions. If a machine is invented that doubles employee productivity, a democratically-controlled workplace might vote to cut the workday in half and keep wages and profits steady. Contrast that with our current system in which employers exercise top-down control over the workplace. When businesses rise to the level of international corporations employers lose all connection to the production process. They simply send their proxies off to represent them at the board meetings. Their contribution is to shuffle down to the ends of their driveways once-a-month in their slippers and their bathrobes and collect a check from their mailboxes. At that point, the only interest these owners have is in maximizing the size of that check. As any of us would, they follow their narrow self-interest. When it comes to making business decisions, their proxies elect CEOs who focus solely on profit in their decision-making. Whereas a democratically-controlled workplace would have other juggling balls to keep in the air besides just profit.

As Marx pointed out, the fact that the consumer base for goods and services is being eroded by the accelerating pace of technology is a huge problem. From the time of the New Deal in the 1930s up until the 1970s, America dealt with this problem by taxing the wealthy. Top tax brackets were taxed at 95% during this period, which many Americans identify as a Golden Age.

The Revenue Act of 1935, which imposed these steep tax rates, was called the “Soak the Rich” Act by those who opposed it. But President Roosevelt saw this tax as the only salvation for a capitalist system that had seized up during the Great Depression. “No one in the United States believes more firmly than I in the system of private business, private property and private profit,” he said. “No administration in the history of our country has done more for it. It was this administration which dragged it back out of the pit into which it had fallen in 1933. If the administration had had the slightest inclination to change that system, all that it would have had to do was to fold its hands and wait—let the system continue to default to itself and to the public.”

FDR’s strategy saw the economy as analogous to the water cycle, in which water evaporates off the ocean and floats as clouds over the mountains, where it falls as rain and begins the long journey back again to the sea via lakes and rivers. During the 1930s, water had pooled up in the coffers of the rich; too much wealth was sequestered in their bank accounts. To get the cycle moving again, FDR transplanted money from where it was pooling to where it was sorely needed. He did this using the tax system.

Since the 1970s, the well-heeled have been using their political influence to roll back those steep taxes. A new solution to the problem of workers affording the products they make was introduced. That solution was credit. Instead of taxing the money out of the bank accounts of the wealthy, they began instead to loan America the wealth we need to consume the goods and services we collectively produce. By the 1980s, the era of the shopping mall, credit cards were ubiquitous. Today, every single category of debt stands at record levels. From credit card balances, to auto loans, to student debt, to mortgages. Even our national debt is out of control; it’s gotten exponentially worse since the crash of 2008. Borrowing money from the ultra-wealthy instead of taxing it from is a solution that can only work in the short term. And by 2008, we could no longer service all that debt.

To understand what happened in 2008, we have to understand the accounting concept of the balance sheet. That is simply assets listed next to liabilities. For you or me, our credit card balance and our home mortgage are liabilities that we pay each month. For the banks on the other side of these transactions, those expected payments are counted as assets. In other words, we account for the promise of all those future payments as if they are already cash in the bank.

In 2008, we finally had to face the reality that huge swaths of home loans were never going to be repaid. Those loans should have been written down and revalued at the actual ability of the borrowers to repay them. In other words, creditor balance sheets should have been reduced to reflect reality. But that would have meant a massive haircut to wealth of the banks and their owners. The politically-connected were no more willing to accept this haircut than they were to accept 95% tax brackets.

So instead, we let the ultra-wealthy transfer what should have been a write-down of their private debt onto the backs of the general public. The apparatus of the Federal Reserve was used to buy huge amounts of their bad debt at face value. The monetization of this debt, euphemistically referred to as “Quantitative Easing”, has been going on ever since—to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars per month. The Fed's balance sheet expanded from approximately $4.2 trillion in late 2019, for example, to over $7.4 trillion by the end of 2020.

Now we’re living in the same bizarre twilight that the Romans did post-410 A.D. One in which everyone knows about the crazy tab being run up over at the Treasury Department. But the banks are so politically well-connected they’ve ensured no one is elected to public office who is willing to talk about it. They are so well-connected that, as Wikileaks revealed, in 2008 the incoming Obama administration submitted his cabinet positions to Citigroup for approval. Right under our noses, the ultra-wealthy managed to transform their private debt problem into a looming sovereign debt crisis that will affect all of us. The sheer quantity of US dollars being printed to prop up the balance sheets of the wealthy means that we have a date with destiny. Eventually, so many trillions of dollars will have been printed that the value of the dollar will collapse and our system of credit will go right along with it.

Here at System Failure, we like to stress the positive. So consider this: we’ve been recklessly printing money and handing it over to the wealthiest among us. And that’s naturally caused an inflation in the price of the things wealthy people buy; things like stocks and real estate. But when the dollar gives in to all this stress, our system of credit and all our savings reckoned in dollars will be gone. After that point, homes trade at prices that reflect what people actually have on hand. At the moment, home prices reflect what the banks loan us. It is our system of credit, not NIMBYism or zoning regulations, that deranges home prices. An entire generation locked out of home ownership could suddenly find that they have access to the space they need to start families. That’s a considerable silver lining to the dark clouds on our horizon.

Of course, chaos is a guarantee when our financial system finally fails. As we wait for a new system of production and distribution to arise and replace the old, there will be breadlines like there were during the Great Depression. But according to the United Way, there are currently 28 vacant housing for every homeless person in America. A collapse of the credit system has massive potential to greatly improve life for the majority of us. In other words, a great shaking of the economic Etch-A-Sketch might be just what the doctor ordered. The passage of old systems into the dustbin of history is a normal part of the millennia-long trend of gradual improvement that characterizes the human story. It’s inevitable. And it’s not something to be feared, except by those who hold positions of privilege in systems past their expiration dates. The central idea behind this System Failure newsletter is that we could have the kind of revolution were there is dancing in the streets and the cafes are open all night.

I appreciate and share your optimistic fatalism, along with the perspective that disruption can create fertile ground for new opportunities to sprout - particularly in the context of remote work.

https://mustardclementine.substack.com/p/reversing-remote-work-would-waste-disruption

Giddy for bread lines and mass suicide, so long as every crack head and miscreant gets their own 2 bedroom detached.