This essay is the third in a five part series. Part 1 is about the ubiquity of debt forgiveness in pre-Greek and Roman societies. Part 2 connects debt to the idea of an apocalypse. Part 3 relates apocalyptic religion to psychedelic drugs. Part 4 focuses on the twin illusions of time and ego. And finally, Part 5 reveals the true meaning of the Holy Grail.

Dionysus & The Gospel of John

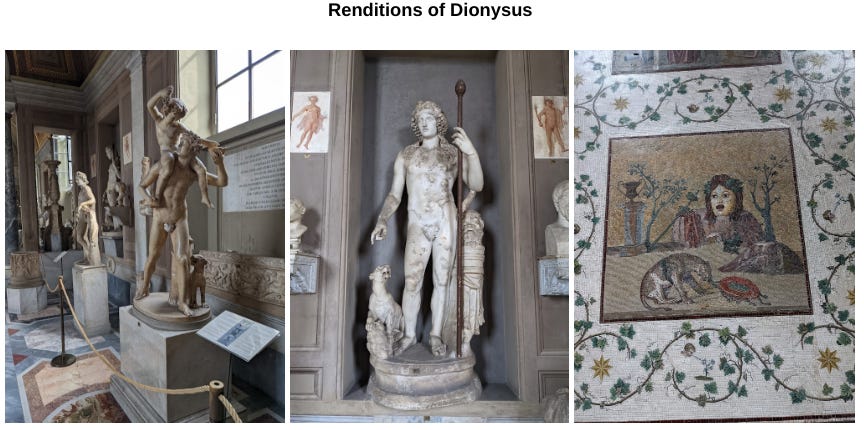

Most visitors can’t help but notice that the Vatican Museum is jam-packed with pagan statues. But before we could ask the obvious question on a recent visit, our guide waved his hand over the array of statuary. As societies ebb and flow over centuries, he explained, traditions are lent and borrowed so that even the gods evolve over time.

To his point, folks generally realize that December 25th is not really the birthday of Jesus. Christmas is celebrated on that date because of the winter solstice. The early church understood that the heathen were more readily converted when they could hang on to their old pagan feast days. Our guide was acknowledging the delicate fact that the transition from paganism to Christianity was often more of a switching of the sign on the door than some sweeping wholesale change.

The Gospel of John is the ultimate example. That’s the gospel where Jesus turns water into wine. Whole chunks of that text are ripped straight out of The Bacchae—an old Greek play about the wine god Dionysus. The very same Dionysus who is unusually well-represented among the pantheon of stone figures at the Vatican. A god who, according to his legend, dies and is resurrected. And who is symbolized by the kantharos cup (here you should be getting some Holy Grail vibes).

What’s the deal with all this wine?

Back in the day, wine was like today’s pizza: a delivery system for other ingredients. At the same time the gospels were being laid down, a man named Dioscorides wrote out an extensive list of all the medicinal effects of every known ingredient. It took up five volumes. He slapped the name De materia medica on it, and the resulting “pharmacopeia” was considered definitive all the way up until the time of the Renaissance. What interests us is that Dioscorides devoted the ENTIRE fifth volume to wine combined with other ingredients. Groovy ingredients like the hallucinogenic mandrake root. The ancient Greeks didn’t drink their wine straight-up. Dioscorides shows us that they regarded it as a mixer for potions of eyebrow-raising potency. These potions—not the contents of the Franzia box in your fridge— is what our friend Dionysus was the god of.

The New Testament was originally written in Greek, and the Gospel of Saint John is a tale with key words and scenes lifted straight out of a famous Greek play about a resurrected god of intoxication. When Greek-speaking people living around the Mediterranean theater caught wind of that, they must have rubbed their hands together with glee…because John’s gospel was telling them that they were about to get some kind of high.

What could the idea of resurrection possibly have to do with intoxication? And if Christianity inherited so many elements from its pagan forebears, whatever happened to this tradition of getting high? Today’s churches, after all, are some of the soberest places around.

To answer these questions, we’ll delve into the psychedelic pre-Christian religions of the Greco-Roman world. Once we understand what the practitioners of those classical religions meant by being “saved”, the Christian notion of resurrection will suddenly take on a whole new meaning. The importance of intoxication, having first been inherited by Christianity and then scrubbed from it, will become clear.

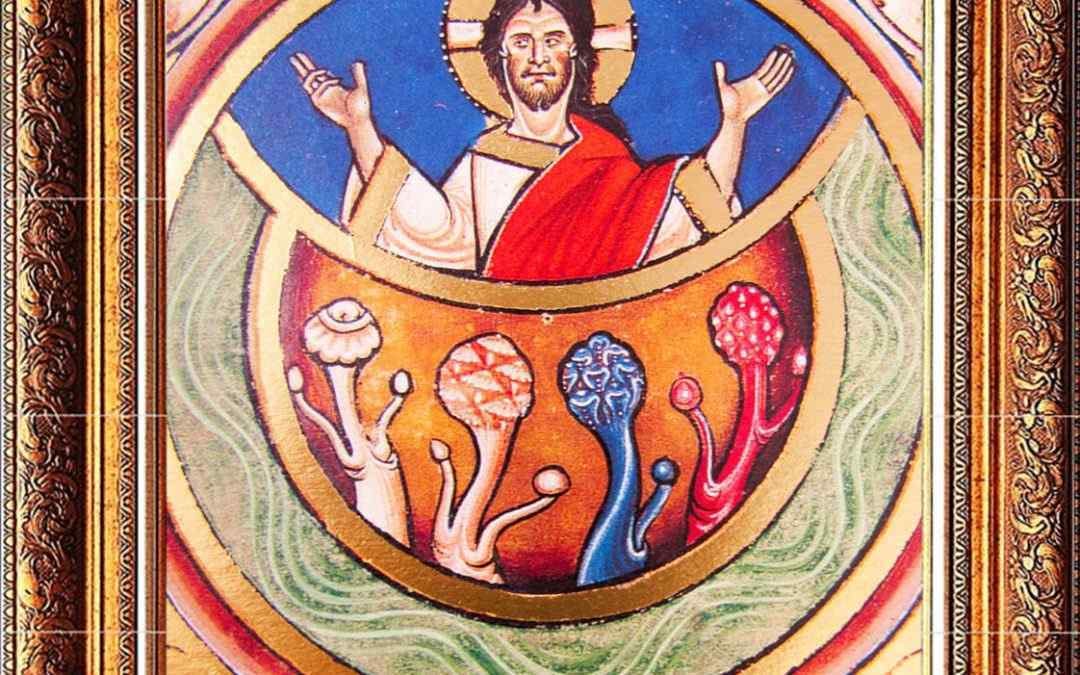

But first, here are some pictures and quotes about Dionysus to transport us back to the furious old days of Classical Greece. Don’t miss Will Durant’s bone-chilling account of Dionysian cult practices...

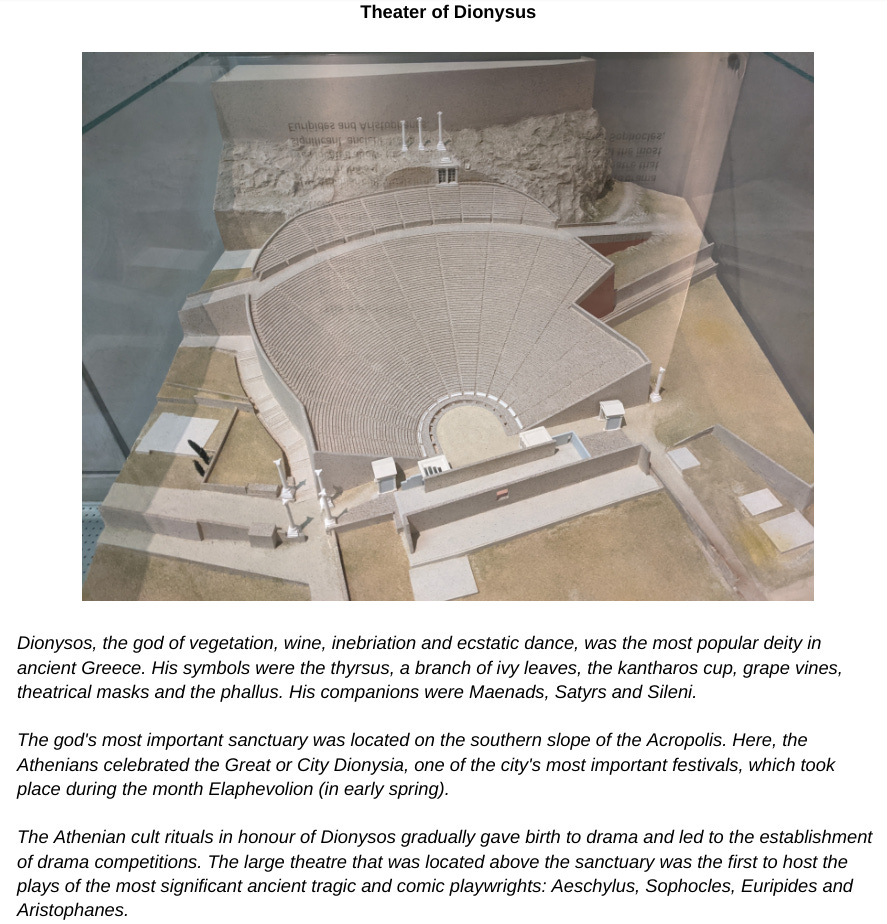

Eleusis & Dionysus

The rites performed at a place called Eleusis were central to the religious lives of the ruling classes of both Greece and Rome. For thousands of years, everybody who was anybody paid a visit to this small town just outside of Athens. From Plato right on up to Julius Caesar, the crème de la crème of the Greco-Roman world were initiated into something called the Eleusinian mysteries. It could not have been a bigger deal; blabbing this mysterious secret was punishable by death.

But then Athens became the world’s very first democracy, and the idea that the famed Eleusinian mysteries should be reserved for society’s upper crust fell out of vogue. It was replaced by the notion that all citizens are politically equal. In a democratic society, it was only a matter of time before the secret was democratized. And when it was, the cult of Dionysus became the populist counterpart to the rites at Eleusis.

So what was in the mysterious potions being served up in ceremonial chalices at Eleusis and mixed in with the wine drank by the frenzied revelers of Dionysus? That’s been an enduring mystery for thousands of years. But the most exciting part of Brian’s Muraresku’s 2020 book, The Immortality Key, is some remarkable new evidence from the burgeoning field of archaeobotany. At a site in Spain where Greek colonists once performed copycat Eleusinian mystery rites, a human jawbone and a ceremonial chalice both tested positive for ergot.

Ergot is a fungus that grows on cereal grains. It’s a magic mushroom. The wildly hallucinogenic ergot is thought to be responsible for causing some of the more bizarre episodes in history, like the Salem Witch Trials. It’s the very fungus that the Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman used to first synthesize LSD back in the 1930s. It’s also highly toxic. Ergot poisoning was known as “Saint Anthony’s Fire” during the Middle Ages because it’s agonizingly painful and often fatal. The secret of Eleusis was the knowledge of how to mix up an ergot potion so that it brought on beatific visions without condemning the initiate to a painful death. For thousands of years this piece of ancient biotechnology was handed down from generation to generation of Eleusinian priestesses. But in the end, the democratization of the Athenian state led to the democratization of the secret of Eleusis—under the guise of the wine god Dionysus.

So what could visionary drugs possibly have to do with resurrection and salvation? The spooky answer to that question has to do with ego. But before we get into that, here are a few more pictures and quotes to give us the flavor of the goings-on at Eleusis. Legendary historian Will Durant, writing at the same time that Hoffman first synthesized LSD, could not have known that visionary drugs were providing the magic. Nevertheless, he managed to leave us a clear description of the psychedelic experience of ego death…

Ego Death

Alcohol disables the part of your brain that makes you nervous. That’s why it’s called “liquid courage”. So fortified, you can give a better wedding toast or make a better overture to that cute girl at the bar. Even though it lowers cognitive function, booze can be a performance-enhancing drug. This pharmacological addition-by-subtraction also works on other parts of the brain. There are substances out there that shut off the ego in the way alcohol shuts off nerves. We call them psychedelics today. And intoxication from those substances was at the core of all the major Greco-Roman religions, including Christianity.

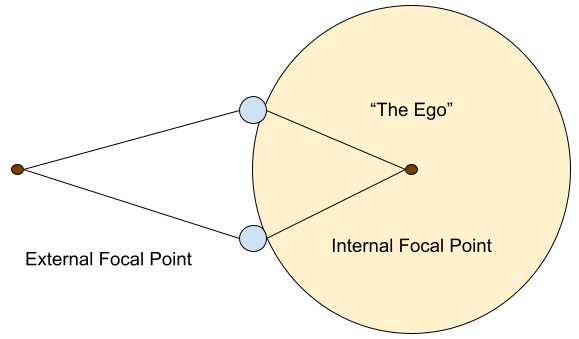

Your ego is your mental conception of yourself. As a subjective observer, you triangulate on external objects by focusing your eyes. When I ask you to focus on yourself, you can only mirror this triangular pattern and interpolate backwards to a reverse focal point behind your eyes. This gives rise to the uncanny feeling that you are riding around inside your head, looking out through your eyes like some kind of windshield. That inverted focal point feels like the seat of your consciousness. It feels like you.

In the physical world, of course, there is nothing behind your eyes but brain meat. But you are not your brain, you HAVE a brain. Your parents didn’t name your brain. They didn’t name your body. They named this spot behind your eyes and acted like that spot HAS a body. Though it’s the most useful of fictions, your ego is entirely a construct within your mind. It’s just the mental reflection of your physical body. You walk around all day behaving as if this reflection is really you, but it’s actually just a phantom. You are no more your ego than you are your reflection in the mirror.

So what happens when your ego is temporarily dissolved? You are, as Will Durant put it, “lifted up out of the delusion of individuality”. You stop seeing yourself as a single person. Instead, you seem to be a progression of people. Like waves lapping at a shoreline, instead of a single wave. Drug-induced ego death (and, later, resurrection after the drugs wear off) brings on this wholesale shift in perspective every time. It’s like taking off a mask you forgot you were wearing. You identify as your ancestors and your descendants all at once. The importance of family suddenly snaps into focus and you feel a swelling desire to sacrifice on behalf of others. Because truly, if you go back enough generations, we are all family. The words "do unto others as you would have them do unto you" from the Sermon on the Mount become a self-evident tautology. This shift in perspective is what the Greeks and Romans meant by being “saved” at Eleusis. Intoxication was at the crux of it. You survive your own death by simply redefining what “you” are. Immortality comes from identifying as a progression of people instead of a single individual.

Christianity & Intoxication

In 186 BC, the Roman senate outlawed the Dionysian cult and 6,000 cultists were put to death. The elite realized that religious practices involving drugs were a threat to their power. Think about it: the state can control individuals through torture and murder, but it has nothing with which to intimidate people who don’t see themselves as individuals. In an act of consummate badassery, Jesus demonstrated this concept by volunteering to have his body destroyed in a gruesome public spectacle.

To fight back against persecution, the cultists switched the sign on their door from Dionysus to Jesus. The Gospel of Saint John was their coded message. That story of death, salvation, and resurrection let Greek-speaking people in every corner of the Mediterranean know that the pirate flag was being hoisted. They moved their wild outdoor observances inside, away from the prying eyes. The consumption of drug-laced wine and ergot-infested bread became a sacramental meal. A meal that lives on in the Latin church as the “Last Supper” (the last meal before ego death). In the Orthodox church, it’s the “Mystical Supper” and to the Russians it’s the “Secret Supper”.

So it was that Christianity inherited the Dionysian elements—including the notion of a magic cup, of resurrection, salvation, and of surviving death. These are all major themes in every Christian church to this day. But the intoxication bit, the part that gives rise to these insights in the first place, was covered up in one final dastardly coup by the elites.

That cover-up goes back to the twilight of the Roman Empire. The economic structure of Rome doomed her to an eventual debt collapse. On the eve of the Fall of Rome, the gap between rich and poor widened into a hopeless chasm. The upstart Christian faith exploded in popularity under those circumstances. It was, after all, a Greek intoxication cult grafted onto the apocalyptic Jewish anti-rich, anti-debt tradition. To the exhausted subjects of a dying empire, a more attractive bouquet of religious ideas can hardly be imagined.

When the end came and the Visigoths pounded at the gates of the Eternal City, the Roman elite dressed up as Christians to save their hides. They adopted Christianity as their state religion, and the Bible was edited and formalized into a state-sanctioned document. Because of its sly and indirect allusions to The Bacchae and to drug-use, the Gospel of Saint John slid into the finalized version. But the Gospel of Thomas didn’t make the final cut of the Bible because it was explicit about Jesus and drugs:

To preserve their wealth, the newly fused church and state rebranded the debt forgiveness demanded by Jesus into forgiveness in the afterlife. To preserve their power, they replaced the ego-dissolving drugs with a Eucharist of regular bread and wine. They sought a monopoly on access to heaven; they couldn’t have people accessing the divine with mushrooms that any fool could pluck in the forest. In short, they un-democratized the mysteries.

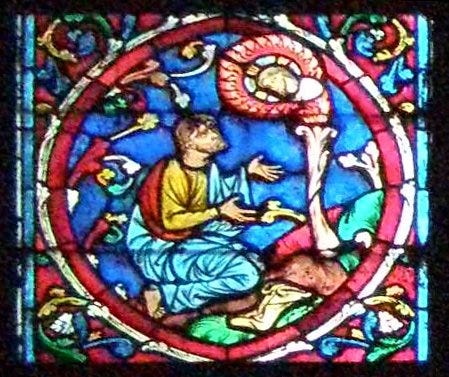

Even though intoxication was formally edited out of Christiantity, everyone knew that visionary drugs had been at the core of that religion. They didn’t forget overnight. It wasn’t until the time of the Inquisition, a thousand years later, that the Church began to pretend that it hadn't originally been all about getting high. That's why, according to Julie and Jerry Brown, you can still find mushrooms in medieval art throughout Christendom:

Today, visionary drugs like mushrooms and LSD have reentered our culture. But they are still demonized by the powers-that-be. Our version of the Roman Senate, the US Congress, has classified these substances as “Schedule I”. That means they supposedly have “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse” and that possessing them is a felony. Research out of Johns Hopkins and NYU hints at their awesome religious power and makes nonsense of this legislation. But of course, the fight over these drugs has always been about power. The competitive hoarding of wealth—for the glorification of individual egos—once brought mighty Rome to its knees. And now that same disease is rotting modern society. The medicine for this disease dissolves the ego growing like a cancer in all of our minds. It’s “high” time we were reacquainted with magic mushrooms and, by extension, our own divinity.