I. Introduction

Our authorities define reality for us. But the ideas they hand down don’t always reflect actual reality. More often, they reflect authority’s desire to remain the authorities.

Christianity is an excellent case in point. The teachings of the Church notoriously depart from actual scripture. The Doctrine of Papal Infallibility is a amusing example. That doctrine lacks any scriptural basis whatsoever. But it serves the interests of the Vatican to have their flock believe they are infallible.

The exclusive divinity of Jesus is the ultimate example of this phenomenon. In a bid to consolidate political power, the early Roman Church asserted the divinity of Jesus—and at the same time made the rest of us out to be miserable sinners. By setting up Jesus as a uniquely divine figure, they awarded themselves a monopoly. And like any good monopoly, this one was highly monetizable.

During the Middle Ages, no one questioned the idea that we are all miserable sinners in need of salvation. They didn’t question the idea that Jesus, being uniquely divine, is our only hope of salvation. And they certainly didn’t question the idea that the Church is the only legitimate connection to Jesus. These three ideas were bedrock reality to Medieval European society because they uncritically believed what the Church told them. The Church took advantage of that trust to make themselves the beneficiaries of a highly lucrative toll booth on the only road to heaven.

II. Roman Society

The Fall of Rome was the historical stage onto which Christianity stepped. The new religion flourished as the Empire crumbled. Starting with Constantine in 337, Roman Emperors bent the knee and accepted baptism into the Church of Christ. But their conversion to the popular new religion was really a ploy to cling to decaying political power.

Accepting baptism meant accepting Jesus as God’s son. That much the Christian Roman Emperors could stomach. But acknowledgement that all of us are similarly children of God would have violated the established political hierarchy they were trying to preserve. So they threw their political support behind select Church Fathers, who were willing to affirm a version of Christianity in which only Jesus was divine. In other words, they propped up their dying empire by setting up the sole road to salvation so that it went through Rome.

III. Divinity

It seems blasphemous to suggest that you and I are every bit as divine as Jesus. But that’s only because we’ve allowed the Church to define blasphemy for thousands of years. Their own foundational text actually supports that notion. It’s right there in the 82nd Psalm—where God says to us “Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High. But ye shall die like men.”

References to the divinity of Regular Joes can be found in the New Testament as well as the Old. In John 10:32, Jesus’ remarkable claim of divinity almost gets him stoned to death by his fellow Jews. But he defends himself with the words “Many good works have I shewed you from my Father; for which of those works do ye stone me?”.

“For a good work we stone thee not,” reply his would-be executioners, “but for blasphemy; and because that thou, being a man, makest thyself God.”

Jesus invokes the 82nd Psalm in his defense: “Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?”. His scolding continues in verses 36: “Say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?”

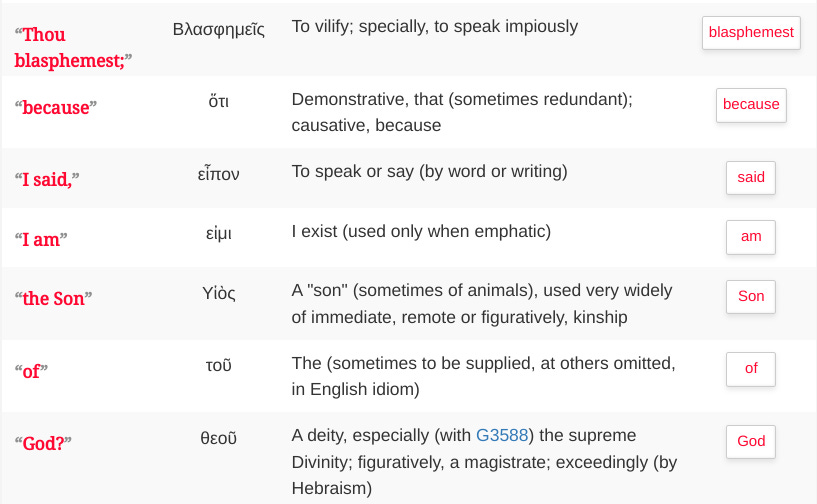

But the original Greek manuscript doesn’t say “I am the Son of God”. As you will see in the translation of Verse 36 below, it says “I am a Son of God”. The word “the” was interpolated by the translators. The change to the original meaning is subtle. But it made all the difference to the Church, whose monetizable monopoly hinged on it.

IV. Saint Augustine

Asserting the exclusive divinity of Jesus was a way for the Emperors of a dying empire to bolster Rome’s waning political relevance. It was an intellectual scam in three parts. First, Jesus was the only road to salvation. Second, the Roman Church is the only legitimate representative of Christ on Earth. And third, we desperately need the salvation Rome offers us. That last piece is why guilt was institutionalized as a virtue in Christianity.

An early Church father named Augustine of Hippo championed the idea of human nature as inherently sinful. He took the idea of sin to the next level. According to St. Augustine, guilt is appropriate even when we haven’t done anything wrong. He made up the idea of Original Sin, in which we’re all stained by the crimes of Adam and Eve. When it came to shame and guilt, Augustine was a true innovator. It’s no wonder he enjoyed the political support of the Roman Emperor Theodosius. To this day, shame is still a fixture in the modern conception of Christianity we’ve inherited. It’s there because it once propped up a collapsing empire.

V. Medieval Society

This constellation of Christian ideas—from the exclusive divinity of Jesus, to the legitimacy of the Roman Church, to the sinful nature of humankind—was a clever scam. One that would outlast the Fall of Rome and become highly profitable during the Middle Ages. That’s when the Roman Church began brazenly charging people for sin forgiveness. The leaders of the Medieval Roman Church couldn’t resist setting up a toll booth on their road to heaven, the exclusivity of which the last Emperors of Rome helped them establish. St. Augustine’s institutionalized guilt motivated their flocks to open their wallets. Making people feel guilty was brisk business. If they recognized their own divinity and stopped feeling so guilty, they wouldn’t be inclined to pay a third party for access to heaven.

The genesis of Christianity into the religion we recognize today was shaped by the collapse of an Empire. And by good old-fashioned greed. It just goes to show how even our broadest conceptions of bedrock reality can be pre-engineered by political authorities to serve their interests. That’s why finance and religion are inseparably intertwined.

V. Modern Society

The Protestant Reformation largely put the kibosh on the sale of indulgences. By asking some tough questions about its corrupt practices, Martin Luther and his fellow malcontents finally shattered the political power of the Roman Church. But none of them ever thought to question bedrock ideas like whether Jesus was the exclusive Son of God or just one of God’s many children.

Neither the Protestant Reformation nor the Scientific Revolution really questioned the doctrine of Original Sin. Today, science is the authority that defines our reality for us, as the Church once did. But our scientists still assure us that—because of a fundamental flaw in human nature—we are facing an imminent judgement day with respect to the climate. They might very well be right. But we should notice that we’re still getting the same apocalyptic yarn spun by the Church for thousands of years. In the 21st Century, St. Augustine still laughs from beyond the grave.

VI. Conclusion

The French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville once called America “the last daughter of the great Roman Republic”. Tracing the genealogy of ideas like Original Sin shows that he couldn’t have been more spot-on; we’re still living in the long shadow cast by Rome.

Virtually everyone senses that we’re in another era of paradigm shift like the Fall of Rome or the Protestant Reformation. It’s in the air. And a re-examination of bedrock conceptions of reality is a key part of any paradigm shift. Some of those conceptions are bound to be mistaken. Many others are bound to be outright scams, like the exclusive divinity of Jesus.

The notion of our common divinity was abandoned during the early days of Christianity—because it didn’t serve elite political and economic interests. Perhaps by re-discovering the divinity within each of us, we finally leave behind the turbulent cycles of Empire and set out together for a better future.